Steering designers toward sustainable solutions

Johan van Niekerk – vanniekerkj@cput.ac.za

Mugendi M’Rithaa – MugendiM@cput.ac.za

Abstract

A failure in ethics is an indication of a fundamental blind spot about the nature of things.

Ethics should never be a listing of minimal (usually negative) standards but rather a way of sensitizing us to nature and the human community (Moore, 2003).

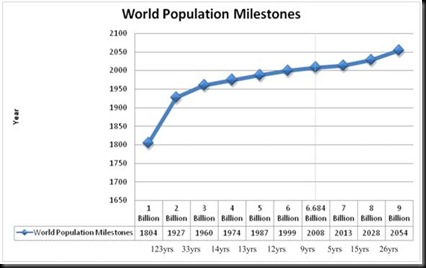

We as Homo sapiens or in Latin "wise humans" have lost touch with our subtle understanding about the nature of things. Globalization and the scale of industrialization required to maintain our booming population have also led us to a new era of ethical behavior. The overcrowding around the watering hole is unprecedented. No model of the past has taken into account an estimated population of 6.684 billion (as of July 2008) and an expected 9 billion by 2054 (UN Population Division, 2001).

It is essential that we relearn how to ‘drink at the watering hole’ in a sustainable and equitable manner bearing in mind that we don’t jeopardize our children’s chances of being welcomed back!

Keywords

Design Ethics, Leapfrog Hypothesis, Moral Psychology, Sustainable Production, Ubuntu.

Introduction

We will discuss the recurring emergence of ethical awareness in design. We will touch on Eastern, Western and African ethics models as well as discussing the traditions that lead to the differences. A designer has a responsibility and should act proactively as an ambassador to the world at large. Designers have the power to act either with wisdom and exercise sensitivity towards sustainability, or to simply maintain the status quo of working towards perpetuating human greed for short-term gain as has been the norm since the Industrial Revolution.

Further, this paper will investigate the (possible) direction of future design pedagogy towards ethical practices within the South African context and the effect of such practices on the design of products. Appropriate methodologies inform the process of making ethical choices towards sustainable solutions that create corporate conscience as well as local and global prosperity.

Allow us to ask a few questions that should set the mood for the rest of the paper. When is an ethical act ethical? What is the difference between morals and ethics? If ethics are subjective how can they play a part in academic discourse? Is ethical design a long term goal? How will this affect each of us individually?

There are as many theories about ethics as there are schools of religion, this is not a chance coincidence. The eons long debate about the nature of divine essence is mirrored in discussions of morality. Humans are the only creatures that have issues of morality as we are the only creatures that live beyond our means. If another species developed beyond the capacity of their ecosystem they would be removed, relocated to, or altered towards equilibrium by the very environments they live in. If we develop the definition of ethos into today’s context then the human race has not only taken over the watering hole but has eaten all the animals, fenced it in, polluted it and is busy moving to the next one.

The Watering Hole

In ethos there are no rules, no listing of negative and minimal standards that the animals abide by. There is an understanding that the right thing is done because continually doing the right thing will result in a radical sense of community. This sense of community around the watering hole leads to a life sensitive to that other than self but still in context of the self. In our anthropocentrism (human-centeredness) we have moved to the top of the food chain but lost our sensitivity to nature and community. That double edged sword makes us human but also is the tool we use to destroy the watering hole.

There is no discussion of removal from society and living in an eco-village, especially not for the majority. We have passed the point of no return; there is no longer enough space for each family to grow a vegetable garden or to harvest their own fuel. In our anthropocentrism we have been forced to become aware of sustainable considerations for environment, products, transport, and so on. We have had to redefine our list of priorities as the world cannot maintain our current vision of ‘utopia’. The mere act of reaction to the global problems is what this paper is about. Any strong reaction is a warning sign that the subtle balance of equilibrium is more lopsided than nature allows. Our blind spot is our belief that we should look out for those nearest and dearest. Our blind spot is not realizing that the more we populate this earth the more we have to act for the betterment of others. Ethics is a method of coming to terms with the fact that although we are alone in this universe (for now), we are all alone together. This sense of a common destiny informs the African concept of ubuntu (which will be elaborated further on).

Ethics and society

Despite the overpowering global drive for sustainability we see very little (in terms of everyday designed products) evidence of reduction, reuse or recycled goods. The drive for sustainability is seen in markets, craft shops or designed goods that place the product out of reach of the intended consumer (Thomas, 2006). According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs Esteem comes after Love/Belonging, then Safety which in turn evolves from Physiological needs. In a country where almost half the people live below the poverty line - where such people barely eke out a subsistence existence, how can ethical choices in sustainable products be a priority? If South Africa (or any other developing nation) does not seize the opportunity to leapfrog into a truly sustainable future, then the road towards socio-economic equity will be fraught with obstacles.

The driving force of globalization and consumerism is free-market capitalism (McCarron, 2003). Admittedly, South Africa does not have sufficient capacity and infrastructure (compared to that of the developed world) to deal with the scale of waste and related issues that certain imported products require. Such products including car batteries, packaging waste, and disposal of CFL bulbs and hazardous wastes, among others.

The discussion focuses on real world ethical design choices that are not only specific to South Africa but are also relevant to the global community. Such choices are essentially qualitative and can be taught. The authors believe that the Green Movement and its partner philosophies are the only long term life plan for this planet but also acknowledge that the nature of societies and its people do not prioritize long term thinking. As Manzini (2006) states, the ethical product guidelines to which we should conform “increase individual freedom and democracy of consumption designing effective, accessible, beautiful products”.

Complexity

Most ethical models, some of which will be discussed later, catered for a time in history very different from today. Deontology, Utilitarianism and Virtue or (Nicomachean) Ethical models were all developed before the population boom of the last century. According to the UN (Population Division) we will have reached a bifurcation point by 2013 and will move from a state of high entropy to a state of low entropy[1]. The population boom will slow down but we should not see a reduction[2] within our life times. This paper is not about population density, we use these statistics to illustrate the basic vision of the watering hole and how it relates to designers. We as designers should be designing for a future world where 9 billion people share the watering hole we call Earth.

Figure 1: World population milestones (UN, 2001)

Ernst Mayr, one of the greatest animal and species evolutionists of our time would say we need to think as a population. Darwin used this thinking (that moved away from essentialism) in his theory of natural selection “changes that prove to be beneficial for survival are preserved and others die out” (Taylor, 2003). We know what sustainable solutions are needed in the design communities yet the market, customers and environments dictate solutions that only cater for short-term gain without seeing the big picture. Our watering hole is now immeasurably more complex but the fundamentals are still the same, we need to drink clean water, we need to share our source and we need our children to be able to share these basic privileges.

The Ethos of Ethics

The differences between morality and ethics are often misunderstood and more often misused. One word is derived from Greek and the other Latin, the interpretation of the two lean toward specific nuances that set them apart (Keown, 2005). Morality has an essential social element and is generally accepted within social contexts, morals dictate the good and bad from a personal standpoint. Ethics tend towards the professional and are usually set in a formal system or code that is accepted and adopted by a group of people making it more objective than morals. Ethics are thus expressions of internalized values whilst morals are externally dictated codes of conduct.

L. Ron Hubbard says “morals are a codification of things which man has discovered to be bad for himself and for others [ethics] in his history, and having discovered that these things were inhibitive to his own survival, he then made a law about them” (Hubbard, 2004). We see a similarity between this in view of the previously cited Darwinian perspective on survival (Taylor, 2003).

Ethics in the West

There are three major models of ethics in the West; we will discuss these now followed by the basic differences in the East and in Africa (figuratively referred to as the South). Deontology which could be described as descriptive ethics had Immanuel Kant as one of its leading proponents. Kant bases his morality on practical reason. He argues that we could never claim to discover an all commanding principle or sets of principles through a moral philosophy, he states that the a priori[3] is the only way not to confuse conditional truths. Kant distinguishes between autonomous and heteronomous, he argues that [autonomous] humans are ‘self-legislating’ wherein they are ‘given’ their moral law by environments and surrounds from child to adulthood, they are then ‘self-motivated’ or ‘self-constraining’ in their dealing with the law (Denis, 2008). In contrast [heteronomous] animals are instinctual and interact with the world through impulses and empirical desires (ibid). The essence of deontology is therefore a promise (rule) of the past which obliges a future action or non-action.

Utilitarianism is a form of normative ethics which proposes broad rules and principles guiding our actions, its goal is to build character by defining the life we should lead. The utilitarianism principle of ‘greatest happiness’ says that actions are right in proportion to their promotion of good consequences (happiness) and wrong when they produce bad consequences (consequentialism). Utilitarianisms’ core principle is beneficence, to be helpful to others according to your means without desire for reciprocation. This principle and system, although virtuous in its idealism, is flawed when looked at from the context of the complexity that the current population brings to the planet. The understanding of what can help or hurt in today’s society is infinitely more complex then it was in the 18th century when utilitarianism was evolving.

Virtue Ethics (or Nicomachean Ethics) has its roots in Plato and Aristotelian thought.[4] Virtue ethics emphasizes moral character or virtues, it does not justify the act in terms of consequences (as in utilitarian) nor does it follow a set of moral rules (as in deontology). In virtue ethics you do the right thing because it is the right thing to do for you and consequently for those seen and unseen around you. Virtue ethics is seen as an opportunity not a demand, its reciprocal law is the more we get from community the more we owe it. The subtlety of a virtue ethics act can be seen in this example. A truthful person does not try and tell the truth, they do not think through the pros and cons while simultaneously qualifying their version of the rules governing the answer. There is no truth for fear of being caught out or because there might be a benefit to telling the truth. A truthful person tells the truth because it has become part of their character. Aristotle (350BC) emphasizes that to know that a virtue is the right thing to do is not a perfectly virtuous act ‘…to know what virtue is not enough; we must endeavor to possess and to practice it, or in some other manner actually ourselves to become good’. Much like life at the watering hole a truly virtuous act does not suffer against conflicting desires. We do, because doing otherwise would cause unbalance. ‘. . . the virtue of the good man is necessarily the same as the virtue of the citizen of the perfect state’ (ibid).

There have been many debates around virtue ethics; they boil down to; what about those that have no propensity toward living a virtuous life? (Hursthouse, 2007). This is a pivotal point that has stopped virtue ethics from being accepted by the masses.

Ethics in the East

Ethical models in the East[5] are difficult to compare to western thoughts. According to David Wong Taoism and Confucianism see the world as inseparable from the journey of knowing ones place in the world (Wong, 2005). Chinese philosophy is designed toward an improved way of life by means of stories and sayings; this is a way of life, a mythology brought about from a young age. Western thinking is debate-based, we qualify statements through reason and argumentation and then lay down a set of rules that will limit potential error. Eastern thought did not have a set of definite principles; each situation required its own resolution depending on the weighing up of judgments. There is a thought that is mirrored in the Daodejing, Confucianism and Buddhism that says the cultivation of the self leads to understanding of the way of the world and our journey in it. This thought is intellectualized by the west but the complex mythology of the early eastern thinking (a thinking that spurned logos) is a barrier that is difficult to overcome. Aristotle moved in this direction when he commented that the young could not comprehend the good in human life because they do not have enough life experience (Wong, 2005).

Buddhists[6] don’t have much to say on ethics because they base every thought on morals. Early Indian texts do not even have a word for ethics, Buddhism could be thought to be egotistic and altruistic; it views moral conduct as it benefits oneself and others. In this perspective it is similar to Virtue Ethics, Keown (2005) suggests that Buddhism belongs to the same family of ethical theory as virtue ethics.

Ethics from an African perspective

The equivalent of virtue ethics in Africa is founded on an age-old concept known as ‘ubuntu’. This ancient and time-honoured anthropocentric philosophy finds myriad expressions amongst different traditional African societies and is being evoked right across the continent to rally up support for participatory developmental projects (M’Rithaa, 2008). The essence of this universally applicable ideal is variously transmitted via folklore and wise sayings or proverbs – a popular medium not very dissimilar to the practice in the East (discussed in the previous section). Consider this example from the Zulu language in southern Africa: “umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu”. This can be literally interpreted as “a person is a person through other persons” (Mbigi, 1997; Creff, 2004; Bhengu, 2006) or to put a twist on Cartesian logic; “We are, therefore I am”, and “we think, therefore I can”. The important point here is that there is an inextricable link between the individual and his or her community. The benefit of voluntarily relinquishing self-serving pursuits and self-indulgence is so that the individual can enjoy a wholesome and meaningful life – an ideal related to the Aristotelian concept of eudaimonia (Hursthouse, 2007) – within a nurturing and supportive community.

We need to state from the outset however that ubuntu does not fit the Western model of formalized knowledge but is flexible as well as being context-, and content-dependent. It is negotiated, adjustable, and thus by extension, versatile. As Mike Boon points out:

Ubuntu is not empirical. It does not exist unless there is interaction between people in a community. It manifests itself through the actions of people, through truly good things that people unthinkingly do for each other and for the community. One’s humanity can, therefore, only be defined through interaction with other… It is believed that the group is as important as the individual, and a person’s most effective behaviour is in the group. All efforts working towards this common good are lauded and encouraged, as are all acts of kindness, compassion and care, and the great need for human dignity, self-respect and integrity (Boon, 2007: 26).

South meets West

As a point of interest, we would like to revisit the Aristotelian virtue ethics, and in particular the three different forms of knowledge attributed to him, namely; episteme; techne; and phronesis (Jönsson 2005: 179). Whereas episteme (from which epistemology or the theory of knowledge is derived) and techne (technology or technique) have found greater acceptance (and indeed some degree of prestige), Jönsson (2005: 179) argues that phronesis on the other hand has been generally unappreciated as “there is no active, contemporary equivalent” meaning assigned to its understanding. Hursthouse (2007: 4) approximates the closest definition of phronesis with respect to ubuntu as “moral or practical wisdom”. As designers trained in an essentially neo-Bauhaus model, the articulation and practice of episteme and techne modes of knowledge happen by default in part due to the inherent philosophical bias towards Western thinking. As we shall argue, phronesis and ubuntu are not as dissimilar as one initially expects. Both are “about values and reality, about people and their actions” (ibid). Further, phronesis “is not scientific in the epistemological sense, since epistemology is primarily concerned with scientific knowledge that is universal, constant in time and space, context-independent and based entirely on analytical rationality. The knowledge relativism that is an integral part of phronesis is thus almost unforgivable in an epistemological approach” (Jönsson, 2005: 180).

This view is supported by Ehn & Badham (2002: 6) who challenge designers to re-interrogate their present notions of phronesis by going back to a time when the “virtue of phronesis had not yet been suppressed”. They argue that phronesis lost out in part due to “the fragile and unpredictable nature of human action” (ibid). Notwithstanding, Ehn et al (ibid) have shown the efficacy of such reasoning to interaction and participatory design wherein they describe phronesis as an “Aristotelian vision of ethical life [and] practical wisdom” (ibid). Jönsson (2005: 181) justifies the renewed interest in phronesis due to the fact that “the epistemological and the technological alone are not able to stand for all that is relevant in […] design”. From the view point of ubuntu, the defence of phronesis would be just as valid for the former. Ehn et al (2002: 6) present the following eloquent rationale:

In phronesis, wisdom and artistry as well as art and politics are one. Phronesis concerns the competence to know how to exercise judgement in particular cases. It is oriented towards analysis of values and interests in practice, based on a practical value rationality, which is pragmatic, and context dependent. Phronesis is experience-based ethics oriented towards action.

We would like to suggest that ubuntu as an African form of ‘ethics by consensus’ relates best to the Aristotelian concept of phronesis. Further, ubuntu is a pragmatic concept that bridges the Western and Eastern concepts of ethics whilst simultaneously offering a dynamic platform for debate and engagement of individuals and their communities (elective or otherwise). As members of our own communities and societies, we cannot stand outside of the same. The responsibility of educators extends beyond interpreting paradigmatic changes and necessitates that we “integrate them into the education system so that they become meaningful, and take root in the consciousness of the people of South Africa” (Tisani 2004: 174). Tisani (ibid) places a greater responsibility on higher education practitioners as the onus on production of new knowledge “falls directly on their shoulders”. Tisani (2004: 175) emphasizes the importance of engaging African indigenous knowledge systems as a transformational tool. Other knowledge systems should not be discarded, but similarly critically engaged with where there is proven efficacy of their value. Higgs (2007: 669) concurs by placing emphasis on reason (or rational thinking) as a universal human phenomenon.

Ubuntu in Education

The ultimate strength of ubuntu is in its pervasiveness and inclusiveness. All the traditional value systems are underpinned by the ideology of ubuntu (M’Rithaa, 2008). In sub-Saharan Africa, it is the relational bond that holds entire communities together through an expanded view of kinship. It is a vital force in a continent that has such a diverse range of cultures, colonial histories, and geo-political realities. Once again, using our analogy of the watering hole, the community negotiates through a public forum of open dialogue (where everyone has equal opportunity) to deliberate on the issues in discussion. The members debate and agree on limiting destructive impulses of individualism through voluntary restraint. These forums are typically dynamic and the exchange is robust wherein members use proverbs, axioms and other verbal/oratory devices honed to perfection over countless encounters. The final resolution on appropriate social intercourse is then accepted by proclamation with every member in the community expected to uphold the shared community-building ideals and values.

The principal goal of subscribing to ethics by consensus is to achieve a collectivized sense of eudaimonia – wherein all members of the community stand to benefit. One very effective device used in enlisting support for ethical behaviour is through constant praise and adulation for those displaying character traits deemed to be desirable for the common good. There is thus an implicit link “between eudaimonia and what confers status on a character trait” (Hursthouse, 2007: 7).

The challenge for us as educators is to align our academic and intellectual discourse within our communities-of-practice and society at large whilst simultaneously taking cognizance of our ethical responsibilities towards our student body, not as their superiors, but in the humility of service to them. As implied herein, ubuntu cannot function without a socially interactive context, and as Creff (2004:8) correctly asserts: “the extent and importance attributed to values shared by ubuntu and servant leadership are significant” – this can only be fully realized in the context of an inclusive egalitarian and open-minded society.

The Rhyme, the reason?

There are as many models of sustainable design practices as there are schools of design. The reason for this is that there can never be one all encompassing system in a world of differing ideologies. Every culture has different needs, each culture uses and misuses the watering hole in a different way depending on what they have, what they don’t have and what they need. Ethics is situation-, culture- and needs-dependant. It is therefore our humble opinion that although the green movements are essential to the survival of the planet (much like deontology versus virtue ethics), the system that relies solely on imposing rules limits the scope and potential of possibilities. As stated earlier, Immanuel Kant insists that there can never be a single principle that governs all sentient beings (Denis, 2008). There is need to balance tolerance for divergence of opinions with a mutual respect and understanding of underlying contextual worldviews and motivations. Just like the herds of wildlife on the African savannah, an enlightened sense of our common destiny demands constructive engagement - even with the most disagreeable of ideological species!

We conclude that without the scaffolding of ethical design to support and nurture the numerous green movements (and other expressions of socially responsibility), such beneficent movements run the risk of becoming dry and uninspiring lists that can only enlist reluctant engagement. Those who are passionate and see a need to push sustainable solutions will most likely be vastly outnumbered by those who do not necessarily follow a moral law or ethical code. Through this exploratory paper, we believe that aligning phronesis with the African concept of Ubuntu and Virtue Ethics could inspire a new model of ethical design, a flexible model that could mobilize the inherent desire for harmony between people, the planet, and the future to create a global watering hole that functions elegantly no matter what herds gather therein. Further, we believe that by harnessing the potential for social good, African economies can indeed leapfrog into a more sustainable production and consumption paradigm without the concomitant wastefulness associated with past and present modes of industrialization and socio-technical development.

We have the opportunity and the duty to instill in designers (within our communities-of-practice) the knowledge needed to take up this most pressing of challenges. Those who influence the production and construction of our world are the advocates of our futures. Victor Papanek (1995: 48) exhorts that “…in the 21st century ethics must form part of design training”. We need to encourage a more holistic and comprehensive view of the potential role of designers to make a difference though inspired informed decisions and ethical choices. We must accept responsibility for the noble calling to which we are drawn as design educators and in so doing play our part in shaping the tools that will ultimately shape the world; to envision for those who have trouble seeing and to futureproof our watering hole for those who will follow in our steps and inherit the only watering hole we know of thus far…

…A design curriculum without an ethical component that enlightens our future world architects, is a sure recipe for disaster.

Works Cited

Aristotle. (350BC). The Nicomachean Ethics Book 2: Moral Virture. Athens.

Bhengu, M.J. (2006). Ubuntu: The Global Philosophy for Mankind. Cape Town: Lotsha Publications.

Boon, M. (2007). The African Way: the power of interactive leadership. Cape Town: Zebra Press.

Creff, K. (2004). Exploring Ubuntu and the African Renaissance: A Conceptual Study of Servant Leadership from an African Perspective. School of Leadership Studies, Regent University. http://www.regent.edu/acad/sls/publications/conference_proceedings/servant_leadership_roundtable/2004pdf/cerff_exploring_ubuntu.pdf [10 March 2007].

Denis, L. (2008). Kant and Hume on Morality. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-hume-morality/ [25 June 2008].

Ehn, P. & Badham, R. (2002). Participatory design and the collective designer. pp1-10 in: T. Binder, J. Gregory, & I. Wagner (Eds). Proceedings of the PDC 2002 Participatory Design Conference, 23-25 June 2002. Malmö.

Higgs, P. (2007). Towards an indigenous African epistemology of community in higher education research. South African Journal of Higher Education/SAJHE, 21(4): 668-679.

Hubbard, L. R. (2004). Morals and Ethics. www.righttraining.net [30 October 2008].

Hursthouse, R. (2007). Virtue Ethics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-virtue/ [25 June 2008].

Jönsson, B., & Certec. (2005). Scientific positioning. pp 177-188 in: B. Jönsson (Ed). Design Side by Side. Lund: Studentlitteratur (Certec/Lund University).

Jung, C. (1995). Jung on the East. (J. Clarke, Ed.) London: Princeton University Press.

Keown, D. (2005). Buddhist Ethics - A very short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

M’Rithaa, M.K. (2008). Engaging Change: an African perspective on designing for sustainability. Proceedings of the Changing the Change (CtC) International Conference, 10-12 July 2008. Turin.

Manzini, E. (2006, August). Design, Ethics and Sustainability: Guidelines for a transition phase. Ezio Manzini's Blog: http://sustainable-everyday.net/manzini/?p=14 [12 April 2008].

Mbigi, L. (1997). Ubuntu: The African Dream in Management. Randburg: Knowledge Resources.

McCarron, C. (2003). Expanding our Field of Vision. Communication Arts, (March/April) 2(319): 16-22.

Moore, T. (2003). The Soul’s Religion. Berkshire: Bantam Books.

Norman, D. A. (2004). Emotional Design: why we love (or hate) everyday things. New York: Basic Books.

Papanek, V. (1995). The Green Imperative: ecology and ethics in design and architecture. London: Thames and Hudson.

Starck, P. (1999). Subverchic Design. London: Thames and Hudson.

Taylor, M. C. (2003). The Moment of Complexity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Thomas, A. (2006). Design, Poverty and Sustainable Development. Design Issues, 22(4): 54-65.

Tisani, N. (2004). African indigenous knowledge systems (AIKSs): Another challenge for curriculum development in higher education? South African Journal of Higher Education/SAJHE, 18(3): 174-184.

UN. (2001). The State of World Population 2001 - United Nations. www.unfpa.org/swp/2003 [06 June 2008].

Varela, F. J. (1999). Ethical Know-How. California: Stanford Universtiy Press.

Wong, D. (2005). Comparative Philosophy: Chinese and Western. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , 4-25.

Johan van Niekerk

Johan van Niekerk is a lecturer at the Department of Industrial Design at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT), Cape Town. He received his Degree in Industrial Design and has worked in industry for close to a decade wherein he has developed a prolific portfolio of products. As well as pursuing studies in Jungian psychotherapy and electrical engineering, he is currently completing his Masters in Higher Education at the University of Cape Town.

This paper is a precursor to his doctorate in Ethical Design.

Mugendi M’Rithaa

Mugendi M'Rithaa is a senior lecturer at the Department of Industrial Design at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT), Cape Town. He has previously lectured in Kenya and Botswana. He was educated in Kenya, the USA, India, and South Africa. Mugendi is passionate about various expressions of socially responsible design, including Design-by-All / Participatory Design; Design-for-All / Universal Design; Design-for-Development; and Design-for-Sustainability.

[1] Entropy could be described as a measure of the disorder of a system. Systems tend to go from a state of order (low entropy) to a state of maximum disorder (high entropy). The moment of truth is when a bifurcation point or turning point is reached.

[2] Barring disasters.

[3] A priori knowledge is independent of experience.

[4] There is much evidence that Nicomachean thought has its roots in ancient Chinese philosophy though this is outside the focus of this paper.

[5] Our references to the East are generalized and based on ideas that were endemic to this region before the pervasiveness of Western thinking impacted that part of the world.

[6] There are an estimated 1.2 – 1.5 Billion Buddhists in the world today.